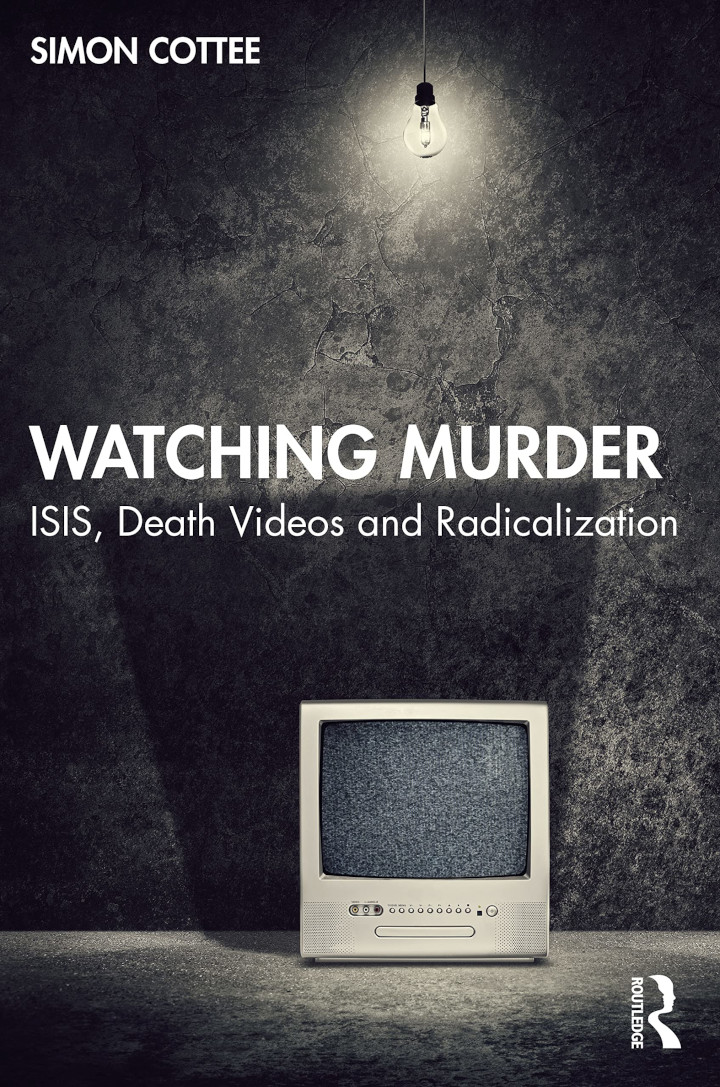

What’s the Right Way to Think About Religion and ISIS?

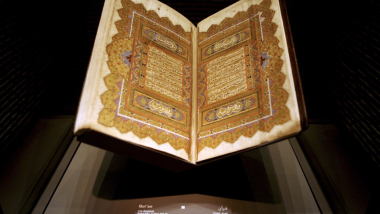

In his Atlantic article on “What ISIS Really Wants” last March, Graeme Wood insisted that “the Islamic state is Islamic. Very Islamic.” Wood’s detractors have been similarly emphatic, arguing that ISIS is a perversion of the Islamic faith. For Wood’s critics, secular politics, far more than religion or religious ideology, is the key to understanding the existence and appeal of jihadist violence.